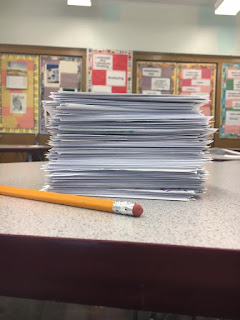

I don't have an answer to either, but maybe here's a start: on Thursday, I told my students that none of us, as yet, had any answers about this election. I made each class spend five minutes writing down every question they could think of on index cards. At the end of the day, I had a towering stack of cards, one that defied any attempt to contain its abundance: rubber bands, paper clips, and folders were all useless and I ended up putting the cards loose in my backpack.

I don't have an answer to either, but maybe here's a start: on Thursday, I told my students that none of us, as yet, had any answers about this election. I made each class spend five minutes writing down every question they could think of on index cards. At the end of the day, I had a towering stack of cards, one that defied any attempt to contain its abundance: rubber bands, paper clips, and folders were all useless and I ended up putting the cards loose in my backpack.About a third of the questions were repeats, wondering how Donald Trump was elected. Most of my students are from Brooklyn, have rarely left Brooklyn; they do not know a world where so many would vote for Trump. Their incredulity rings clear in their questions -- why? how? What will happen now?

Other questions, though, get deeper. My students are smart, perceptive, naive, funny and afraid. Some questions dig deeply into policy and politics; others reveal vast, cavernous fears. A sampling, presented without further comment:

"Was Hillary a better candidate?"

"How important is a president?"

"How can we save our friends from being deported?"

"Trump has no knowledge -- why do we need knowledge to gain a career, then?"

"What positive things is he going to do?"

"Why this type of thing makes me so sick?"

"Is everything going to be ok?"

"Why didn't my father vote?"

"Is this our country? Or theirs?"

"Why are voter id laws so controversial?"

"What the fuck is wrong with people?"

"Why can't we lower the voting age?"

My students have questions, and it makes me hope.

And maybe the answers start here: on Wednesday, my school went on advisory field trips. This was a stroke of possibly-unplanned genius, because I'm not sure if any of us was truly capable of holding it together in the classroom at that moment.

My tenth grade advisory paired with a seventh grade advisory, and we went to see The Education of Mohammad Hussein at BAM, a documentary about a Muslim American boy in Detroit in 2012. During the panel discussion afterwards, the teenagers -- Muslim and non-Muslim alike -- spoke, incredibly, of hope, of coming together.

"I can't believe that pastor in the movie burned the Qu'ran," a non-Muslim girl said, "That was so disrespectful, and I'm so angry."

"But there are good Christians as well as bad Christians," a Muslim girl said.

"We need to remember that we have more in common than we have differences," another girl said. "We are not alone."

She's right. That is real and it is true, and it swells my heart that these teenagers went immediately to places of unity rather than division.

But then there's this, also real, also true: later, in Shake Shack, a construction worker shoved my fellow teacher's chair, angrily, deliberately. She is from Brooklyn, born and bred, and she is also Muslim and wears the hijab.

"Miss," said one of my tenth grade advisees, a Muslim boy who is suspended approximately 30% of the time for getting into fights, usually when he feels overprotective of his friends, "...did he just shove you?"

"No, no," the teacher said, "It's fine. Nothing happened. It's okay. It was an accident."

The construction worker continued to glare at her from across the Shake Shack, and she decided to leave and bring the kids to Chuck E. Cheese. Just in case.

What terrifies me most about this election is that there are true racists in this country that feel they have been given permission to be their most hateful, violent selves. There are xenophobes who now feel that is okay to bully and harass those who they believe to be immigrants. There are men who have been given carte blanche to fuck with women by our future Commander in Chief. It was bad before Trump was actually elected, and it's worse now.

In the days since Tuesday, my facebook feed has been flooded with incidents reported by my former students: one girl's father was told to go back to his own country. Another girl's friend was cornered in a parking lot by men who crowed about Trump's victory and called him a faggot. I see something new at least every day, and this is just the people I know.

And on Tuesday night, I wasn't really surprised. I was appalled, and I was shocked, and I was angry at how little I was surprised and I was angry at the part of me that was at all surprised.

Because here's the thing: what this election really reveled, to a lot of liberal white people, is how tolerant of racism we still are as a nation. As a straight white person, I do not have the same experience of this country that people of color or members of the LGBTQ community do. I do not fully realize the harassment that is often their version of normalcy. And as a woman, I know that men do not have the same experience of this country as I do.

Think about these text message conversations -- which happened only two days apart -- between me and my friend. When I tell this story to straight white guys, they look shocked. (Which is fair! I was shocked when it happened to me!) But when I tell women, they are sympathetic and worried for me, and not particularly surprised.

Similarly, when one of my friends of color reveals the race-based harassment that is normal to them, look at my reaction in the text messages: I am goldfish-shocked, appalled that this happens, that there are people who do this still, regularly, in New York, in Brooklyn. And I'm shocked every time.

We have different realities in this country. There's a reality that I live in as a liberal white woman, certain, sure that other women could never support a man who reeks of xenophobia and brags of sexual assault, unaware that for 53% of white women voters in this country, self-interest eclipses solidarity.

There's the reality I live in as a teacher, believing in my students' hope and in their despair, clinging to the idea that we have more that connects us than that separates us.

There's the reality that the rest of the adults in that auditorium at BAM felt, that these kids are beautiful and naive and there are other adults out there who are trying to destroy them.

There's my fellow teacher, lying to a student about the goodness of the world to keep him from fighting in a Shake Shack, and there's the construction worker, in a reality where a fellow Brooklynite in a hijab is threatening enough to him that he needs to show her who's boss by driving her out of the restaurant.

This is us, in this country: women and misogynists and racists and people of color and white people and straight people and homophobes and LGTBQ and men and feminists and immigrants and xenophobes and poor people and rich people and desperate people of all stripes, all thrown in here together. This is us, and our relative versions of reality are not allowing for each other's humanity.

There's been a lot of talk in the past week about trying to understand the Trump voter and talking with them to understand their point of view and I agree that there needs to be conversation. But if some who voted for Trump would be horrified to consider themselves racist (and I think they would), they must not truly understand what it's like to be a person of color in this country. They were willing to overlook his racism and xenophobia because of the things they liked about him and didn't like about Clinton, which indicates that they either don't understand how bad racism and xenophobia can be for those who have to live with it every day, or they don't care.

When I choose to have hope -- when I choose to believe in my students' version of reality -- I believe that it's because they don't understand.

When I choose to listen to American history, I believe that perhaps they never will.

It's really, really hard to hope right now.

My students, my fellow adults -- we all know what could happen.

We could listen to each other's realities, try to merge them into some coherent whole.

We could pull some conciliatory bullshit where, in the name of unity, the realities of people of color and LGBTQ individuals and women are ignored or diminished once again.

We could, as my students say, come together, realize that we have more in common than we have differences.

We could ignore those differences completely, forget to watch out for each other on the subway, forget to remember that we live with different challenges and different dangers, close the doors to each others' schemas.

Those of us who are relatively privileged by virtue of race, gender or class could actually listen to those who are not -- without judging, without doubting, without resisting.

We could. Any of this, we could.

It's an individual choice, and it happens over and over in every moment.

It's a communal choice, and we might never get another chance.

No comments:

Post a Comment